It all started so well. In 1946, the National Health Service Act was published, and on the 5th July 1948, the NHS created. Welcomed, fêted, needed. From the idea of universally available healthcare regardless of wealth, the NHS was initially based on three core principles: that it met the needs of everyone; that it be free at the point of delivery; and that it be based on clinical need, not ability to pay. Today, the NHS is a different beast, facing many new challenges. Stemming from extensive discussions with staff, patients and the public, these three guiding principles have expanded to seven principles that are still underpinned by core NHS values (1).

- Principle 1. The NHS provides a comprehensive service available to all.

- Principle 2. Access to NHS services is based on clinical need, not an individual’s ability to pay.

- Principle 3. The NHS aspires to the highest standards of excellence and professionalism.

- Principle 4. The NHS aspires to put patients at the heart of everything it does.

- Principle 5. The NHS works across organisational boundaries and in partnership with other organisations in the interest of patients, local communities and the wider population.

- Principle 6. The NHS is committed to providing the best value for taxpayers’ money and the most effective, fair and sustainable use of finite resources.

- Principle 7. The NHS is accountable to the public, communities and patients that it serves.

Aspiring to excellence and attempting to meet such high expectations does not come cheap – there is a constant battle to maintain much-needed services in the face of financial cutbacks. But this is not new, almost from day one, the government was looking at ways to save money; the Guillebaud Report of 1955 found that in relative terms, NHS spending had fallen from 3.75% to 3.25% of Gross National Product (GNP) and that capital spending was running at only 33% of pre-war levels.

Governments continued to tinker with the NHS; cuts, changes, Acts, and reorganisations have happened almost on an annual basis since 1948. These can be viewed on an excellent Nuffield Trust info-graphic (2). Examples include:

- 1973 – NHS Reorganisation Act.

- 1983 – Griffiths report commissioned to explore staff and other resource efficiencies.

- 1990s – split between purchasers and providers of care, GP fund-holders and a state-financed internal market to drive efficiency, the Patient’s Charter, NICE & NHS Direct established, GP fund-holding abolished, primary care groups (PCGs) established.

- 2000s – 10-year plan implemented (modernisation, investment & reform), SHAs, PCTs created, and Wanless report recommends investment in NHS. In 2003 after reorganisation, foundation trusts established, then practice-based commissioning introduced, followed by the New NHS (2013, resulting from Health & Social Care bill), the Five Year Forward View (2014) and in 2015, the launch of devolvement in Manchester.

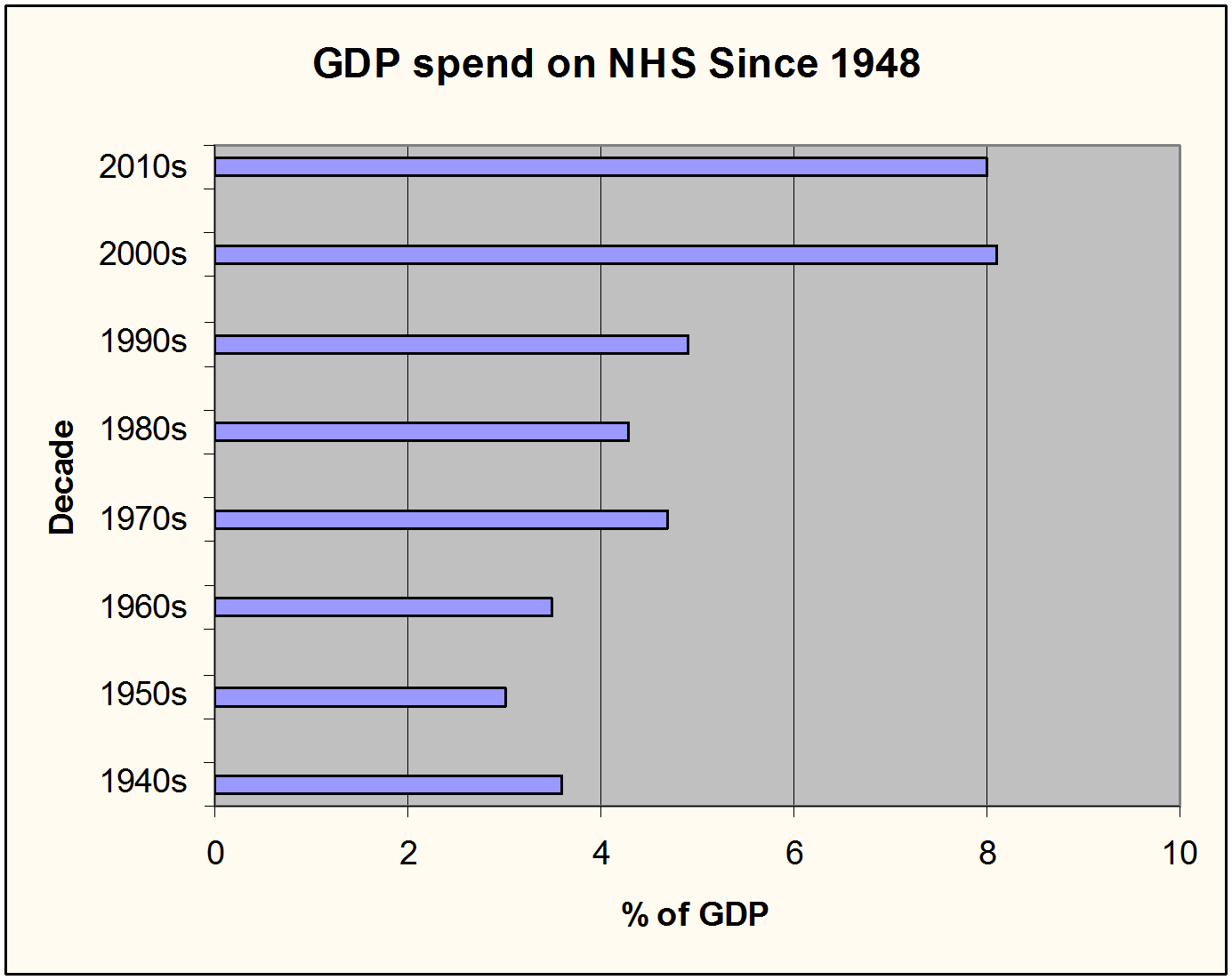

It seems that successive governments have almost been in a classic abusive relationship pattern with the NHS – “I only batter you because I love you…”. While waxing lyrical about the NHS to the rest of the world, in reality, they want savings to be realised and to contribute less to its running. The latter shouldn’t be too difficult, though. Figure 1 shows approximate GDP spend on the NHS since inception (Chantrill 2015).

Figure 1: GDP spend on NHS since 1948 (3).

At Eight percent GDP, current NHS spending is at its highest, According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) figures, UK spending is lower than other 15 other OECD countries, on a par with five, and above 11 others (4). However, the current Government has pledged to ‘invest’ £8bn pa into the NHS until 2020, the question is – can we stop money from leeching out of the NHS?

It would appear not. In 2015, NHS organisations in England ended the financial year with a total deficit of £822m, compared with £115m the previous year. As a result, the NHS regulator, Monitor and Secretary of State for Health, Jeremy Hunt, have thrown their toys out of the pram, with Mr Hunt, in particular blaming everything from agency staff costs to consultants playing golf (instead of working seven days per week). Foundation trusts were told by Monitor that their financial forecasts for the next year were untenable and further savings must be made on top of the £22bn they need to save over the next 12 months (5).

Does the government have a point? Carter’s interim report on NHS efficiency appears to support this (6). For example, the review team has found:

- A wide variation in spending on medicines, everyday healthcare items and on NHS facilities, including maintenance and heating, between the 22 NHS Trusts studied.

- A potential saving of £5bn a year on NHS workforce and supplies.

- An increases in hospital staff efficiency by just 1% could save the NHS around £400m per year.

- A high level of inefficiency in NHS staff management; one hospital was found to be losing £10,000 a month in workers claiming too much leave.

- Inconsistent costing for elective surgical procedures, such as hip operations (sometimes costing twice as much as they should).

A lack of research into cost-effective surgical implants. For example, more expensive hip joint prostheses did not last as long as less expensive ones, resulting in more hip replacements and hospital admissions. This single example costs the NHS an extra £17m each year.

Recommendations included in the interim report (5) include:

- Better use of NHS staff through flexible working and better rostering.

- Better use of prescribed medicines; for example, one NHS Trust saved £40,000 a year by using a non-soluble version of a medication.

- More savings made on hospital items such as aprons, gloves and syringes. (For example, latex gloves costing £5.44 a box at one hospital are bought for £2.39 in another).

- The use of a single electronic ‘catalogue’, facilitating more ‘competitive’ NHS purchasing.

Inefficiencies contribute to deficits, so can better management of NHS resources make substantive savings without affecting patient care? Probably, examples of wastage include the use of specialised equipment like imaging machines only on a Monday to Friday basis, and the overuse of agency staff (across all aspects, cleaners, nurses and drivers). Addressing these issues is critical; increasing running costs as well as and rising indirect costs such as clinical negligence are not sustainable. The leakage of money out of the NHS points to poor management and inefficiency and calls to question whether improvements in the running of NHS should be the government’s focus, rather than financial cutbacks. In part II (“Fixing the NHS”), Healthcare Arena explores NHS management, cutbacks and efficiency to ask if the organisation as a whole really needs fixing.

If you would like to comment on any of the issues raised by this article, particularly from your own experience or insight, Healthcare-Arena would welcome your views.

References

- The NHS Constitution. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/480482/NHS_Constitution_WEB.pdf Accessed December 2015

- Nuffield Trust. The History of NHS Reform. 2012. http://nhstimeline.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/?gclid=CKDAvbrttMcCFVdAGwodex8Bfg Accessed August 2015

- Chantrill C. UK Public Spending since 1990. http://www.ukpublicspending.co.uk/spending_brief.php Accessed August 2015

- The King’s Fund. Health care spending compared to other countries. 2015. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/health-care-spending-compared. Accessed August 2015

- Parnham D. The Carter Review. Procurement in the NHS. HealthCare-Arena. 20th July 2015. https://healthcare-arena.co.uk/the-carter-review-procurement-in-the-nhs/

- Department of Health: NHS Procurement. Review of Operational Productivity in NHS Providers. Interim Report. June, 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/434202/carter-interim-report.pdf