Liver disease is the fifth largest cause of mortality in England and Wales, after heart disease, cancer, stroke and respiratory disease. In the UK, liver disease is increasing, while elsewhere in Europe, it is decreasing (1). But this year in the UK, there have been some remarkable and rapid advances in the diagnosis and treatment of a serious and often undiagnosed cause of chronic, debilitating and lethal liver disease: hepatitis C infection.

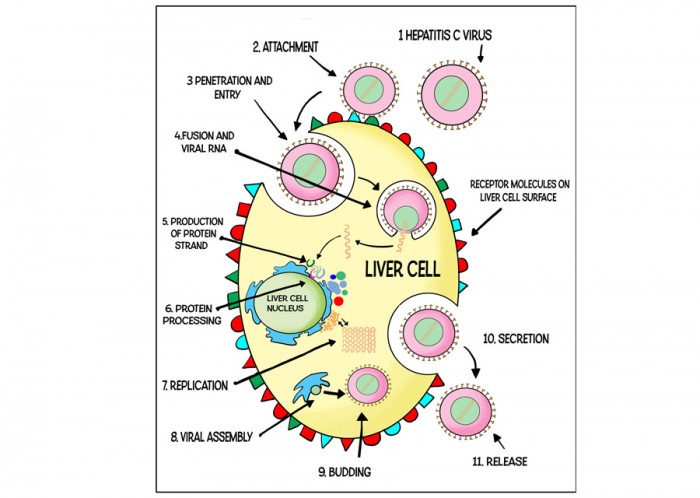

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted in the blood. In the UK, HCV is usually transmitted by sharing needles to inject drugs, but it has also been reported to be transmitted via unsterilized tattoo needles and, rarely, by unprotected sex. Thousands of people were also infected accidentally through contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 20% to 30% of cases, acute HCV infection resolves in a few months, without major symptoms. If the disease becomes chronic, as it does in 75% of untreated individuals, it can lead to liver damage, liver failure, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer. One in three people infected with hepatitis C will develop liver cirrhosis, and some will get liver cancer. For these chronic effects of HCV infection, liver transplantation is the only treatment option. A liver transplant costs the NHS more than £50,000.

Until irreversible liver damage develops, an infected person may not know that they are infected with HCV hepatitis C; this is why this infection has been called, ‘the silent killer’ (2). Hepatitis C genotypes 1 and 3 account for the majority of chronic hepatitis C cases in England (46% and 43% respectively). Hepatitis C genotype 4 accounts for around 4% of cases of chronic hepatitis C (3).

The Hepatitis C Trust sponsored an independent Technical Policy Report on hepatitis C, which was published in 2014 (4,5). Using a cohort simulation model the findings of this Technical Policy Report predicted that unless treatment patterns changed, the overall prevalence of HCV infection would increase from 0.44% in 2010 to 0.61% in 2035 (5). These figures equate to an increase in the number of people living with HCV infection from around 265,000 in 2010 to 370,000 in 2035 (5). This rise in the prevalence of infection would be associated with an increase in healthcare costs, from £82.7-million in 2012 to £115-million in 2035 (5). Productivity losses were estimated to rise from between £184-million to £367-million in 2010 to between £210-million to £427-million in 2035 (5).

Also in 2014, Public Health England estimated that about 216,000 people in the UK are chronically infected with HCV (3,6). New diagnoses of HCV infection reported in England rose from 7,892 in 2010 to 9,908 in 2011 (6). In the UK, the number of hospital admissions for end-stage liver disease relating to chronic HCV infection, rose from 612 in 1998 to 1,979 in 2010 (6). Deaths due to hepatitis C rose from 98 in 1996 to 323 in 2010 (6). Analysis of registrations for liver transplants due to hepatitis C-related liver cirrhosis rose from 45 in 1996 to 101 in 2011 (6).

It has been the appreciation of data such as this that has brought about the dramatic change in NHS policy towards chronic HCV infection during the past year (5,6).

At this same time, there have been some developments in the treatment of acute HCV infection. The aims of treatment are to clear the virus from the patient’s blood, to prevent the progression of liver disease, and to prevent viral transmission. A recent study has shown that if HCV infection is diagnosed early, treatment of acute HCV infection with Peginterferon alfa-2a injection is an effective monotherapy, with ‘cure’ rates of greater than 85% (7). ‘Cure’ is defined as having no HCV detectable in the blood, 12 weeks post-treatment completion. Chronic infection remains a problem when the acute phase is undetected (‘silent’) or unresponsive to acute treatment.

Until recently, the only treatment options for chronic HCV infection have been based on pegylated interferon-alpha-2a injection in combination with the viral nucleoside inhibitor, ribavirin. This treatment is associated with side-effects including fever, joint pain and fatigue and is limited by the need for weekly injections, regular monitoring, and long treatment duration. There is now a range of new oral treatments available for chronic HCV infection. These treatments are well tolerated and have been shown to be effective in chronic infection, but they are very expensive.

In 2014, NHS England published a factsheet and recommendations for improving the diagnosis of HCV infection (8,9). In 2015, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) produced its latest Clinical Practice Guidelines with recommendations for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection, which included the use of the new, oral treatments (10,11).

In February 2015, Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir, Gilead) and Olysio® (simeprevir, Janssen) were recommended for use in the NHS by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) with the publication of the NICE technology appraisal guidance (TA330) (12,13). Harvoni® (sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, Gilead), has received tentative approval for NHS use from NICE (12,13). Exviera® (dasabuvir, AbbVie) and Viekirax® (ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, AbbVie), are yet to be appraised.

In June 2015, NHS England announced the decision to increase the available budget to fund new treatments for chronic hepatitis C to £190-million; this is a rise from the budget of approximately £40-million made available in 2014 (14). The announcement was accompanied by a policy statement by NHS England regarding the treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C infection and liver cirrhosis (14,15). Under NHS England’s Early Access to Medicine’s (EAMS) Scheme, there are approximately 3,500 patients with advanced liver disease and liver cirrhosis, caused by HCV infection who are expected to access the treatments in 2015 (16).

Also in June 2015, NHS England’s Clinical Reference Group for Infectious Diseases published a Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement on the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in patients with cirrhosis (17,18). The NHS funding recommendations support the following drug treatments:

- Exviera® (dasabuvir) and Viekirax® (ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, AbbVie).

- Olysio® (simeprevir, Janssen).

- Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir, Gilead) and Harvoni® (sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, Gilead).

- Daklinza® (daclatasvir, Bristol Myer Squibb).

These oral, short course, interferon-free treatments are now approved and commissioned for patients in England with genotype 1a and genotype 1b HCV infection, for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in patients with cirrhosis and advanced liver disease. Following granting of an EU Marketing Authorisation (MA) from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), Viekirax® (ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir) and Exviera® (dasabuvir) have been available in the UK since January 2015 (19).

Although Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir) has been hailed as a treatment breakthrough for chronic hepatitis C, there are concerns about the very high cost. The cost of Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir) is £1-billion for every 20,000 people treated. NICE recommends that Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir) is cost-effective because it provides treatment for people who would otherwise cost the NHS even more (8).

Campaigns continue to press the drug companies to lower their prices. Gilead, the manufacturer of Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir), are offering a price in the UK of almost £35,000 for a 12-week course; many patients will require a 24-week course, with a total cost of £70,000 (9).

NHS England is running a parallel competitive tendering process, to seek to bring down the price of these very expensive new drugs (10,20). Implementation of the outcome of this process and further treatment guidance is scheduled for August 2015 and throughout 2015.

The rapid developments that have occurred this year in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C provides an example of how the NHS can and does work to put patients first. This year, 2015, will bring even more interesting developments in the availability of treatment for the chronic effects of hepatitis C infection.

If you would like to comment on any of the issues raised by this article, particularly from your own experience or insight, Healthcare-Arena would welcome your views.

References

(1) Public Health England. 2014. Hepatitis C in the UK. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/33711 5/HCV_in_the_UK_2014_24_July.pdf Accessed June 24, 2015

(2) Strudwick P. The Guardian. Hepatitis C: Hunting the Silent Killer. Feb 25, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/feb/25/hepatitis-c-hunting-the-silent-killer Accessed June 24, 2015

(3) Public Health England website. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/public-health-england Accessed June 24, 2015

(4) Hepatitis C Trust website. http://www.hepctrust.org.uk Accessed June 24, 2015

(5) Technical Policy Report. Hepatitis C. A projection of the healthcare and economic burden in the UK. 2013. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/TR1300/TR1307/RAND_TR1307.pdf Accessed June 24, 2015

(6) Public Health England. Hepatitis C in the UK. 2014 Report. The most recent national estimates suggest that around 214,000 individuals are chronically infected with hepatitis C (HCV) in the UK. July 28, 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hepatitis-c-in-the-uk Accessed June 24, 2015

(7) Dieterding K, Gruner N, Buggisch P et al. Delayed versus immediate treatment for patients with acute hepatitis C: a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2013 Jun;13(6):497-506. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(13)70059-8/fulltext Accessed June 24, 2015

(8) NHS England website. http://www.england.nhs.uk Accessed June 24, 2015

(9) NHS ENGLAND. 2014. Factsheet: Testing for and improving diagnosis of hepatitis C virus (HCV). Available: http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/pm- hepatitis-c-fs.pdf Accessed June 24, 2015

(10) European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) website. http://www.easl.eu Accessed June 24, 2015

(11) European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). Clinical Practice Guidelines: EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C, 2015. http://www.easl.eu/medias/cpg/HEPC-2015/Full-report.pdf Accessed June 24, 2015

(12) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) website. http://www.nice.org.uk Accessed June 24, 2015

(13) NICE technology appraisal guidance (TA330). Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir) for treating chronic hepatitis C. Published February 2015. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta330 Accessed June 24, 2015

(14) NHS England. News release. Thousands more patients to be cured of hepatitis C. June 10, 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2015/06/10/patients-hep-c/ Accessed June 24, 2015

(15) NHS England. NHS Commissioning. http://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/group-b/b07/ Accessed June 24, 2015

(16) Early Access to Medicines Scheme (EAMS): scientific opinions. Published June 3, 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/early-access-to-medicines-scheme-eams-scientific-opinions Accessed June 24, 2015

(17) Clinical Reference Groups: A Guide for Clinicians. Clinical advice to the NHS Commissioning Board for the strategic planning of Specialised Services. First published: January 2013. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/crg-guide.pdf Accessed June 24, 2015

(18) Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement. Published June 12, 2015. http://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/06/hep-c-cirrhosis-polcy-statmnt-0615.pdf Accessed June 24, 2015

(19) European Medicines Agency website. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/ Accessed June 24, 2015

(20) NHS England competitive tendering process. NHS Supply Chain. https://www.supplychain.nhs.uk/suppliers/tendering-and-contract-process/ Accessed June 24, 2015